The following article was written by Dennis Wesley, an independent researcher and blogger whose interests lie in interdisciplinary practices and methods, especially those that bridge the gap between STEM and the Humanities. More on his personal blog Science and Arts Education.

Chess is one of our oldest games and as with most long-lasting entities, the game has undergone many changes over the years, influenced even by such factors as societal progress and politics. Chess has passed through different societies and cultures and the game has been played and perceived differently in different settings. Today, chess is one of very few board games accorded the status of sport in addition to also being promoted as a hobby that improves players’ acuity.

Its long past is testament to the game’s undeniable allure: for it is essentially a battle without the violence. In place of the physical battle’s brutality, we have the electric stillness and silence of two opponents locked in mental combat. One cannot be a competitive chess player without the ability and willingness to concentrate well and for long periods of time. That competitive chess is played in front of an audience only adds to this challenge; in the language of psychology, chess challenges its players on the cognitive as well as the behavioural fronts: players have to either tune out the spectators or find ways to feel spurred by being watched and scrutinized by the spectators, while also having to constantly read their opponent’s moves and gauge if and when they have to improvise. Chess can be silent, riveting theater.

The Development of Chess

Chess has been governed by different rules in different cultures, which is to say, the pieces moved differently in different versions. Pieces were also accorded more or less importance and even had different shapes and names. For instance, the Queen, now understood to be the most powerful piece on the board, did not exist in the earliest recorded form of chess, which was called Chaturanga, a version of the game played in seventh-century India. After their exposure to the game, the Persians added a piece they called the Firzan (counsellor), and this piece was subjected to more changes by Europeans during the 1400s. In the process, the gender of the counsellor changed and this new piece with vastly increased powers became the Queen. Indeed, this modification is believed to be a reflection of the rise of powerful female rulers, like Elizabeth I, in Europe at the time.

With the introduction of the Queen and an increase in the Bishop’s range of movement (earlier the Bishop could jump only two diagonal squares in one move), chess gameplay began to resemble what it is today even as rules and moves were added, altered or eliminated along the way.

The pieces were also designed differently (that is, they looked different) by different cultures. How the pieces looked was also a function of the predominant cultural ideas of a given time period and region. In general, the design tended to alternate between elaborate and simple. The modern set was standardized in the nineteenth century in England; though designed by Natheniel Cooke, it is known as the Staunton set since it was promoted by Howard Staunton, who was regarded as the world’s best player at the time.

The Evolution of Chess Culture

Even as chess changed and developed over time and across cultures, it has nonetheless also had its own culture built around it, an ethos of partaking in and appreciating all that the game has to offer. It has been different things to different people at different times: a form of coming together, a tool for strategizing, a hobby, a game, an art form, sometimes even a sport played with scientific, unrelenting meticulousness.

However, the most recognizable form of chess culture is associated with chess as a sport. The first formal world championship match was held in 1886. Prior to this, matches were held informally, though the winner was nonetheless regarded as the world’s best player. The first informal match was held in 1834 between Charles de la Bourdonnais, a French player, and Alexander MacDonnell, an English player. Bourdonnais won the match and held the unofficial World Champion title until his death. Staunton succeeded him and was instrumental in not only standardizing the chess set, but also in establishing stakes games in chess and developing uniform rules.

Around the same time, the tournament style of play in chess was taking form in London and this began to attract the attention of Americans as well. The first American chess legend to emerge was Paul Morphy, who defeated Adolf Anderssen, the then unofficial world champion. Morphy‘s aggressive style of play, coupled with his personal struggles stoked our culture’s fascination with genius and our tendency to associate genius with tragedy.

In 1886, Austria’s Wilhelm Steinitz was crowned the first official world champion. The formalization of the title led to norms being laid out to determine how the matches would be played and who would be allowed to challenge the holder of the title. National federations and associations of chess players oversaw this process till 1924 when, tired of problems and controversies cropping up, the World Chess Federation, or FIDE (the French acronym), was established in Paris. This body assumed the responsibility of awarding the World Championship, arranging matches and determining and enforcing the rules.

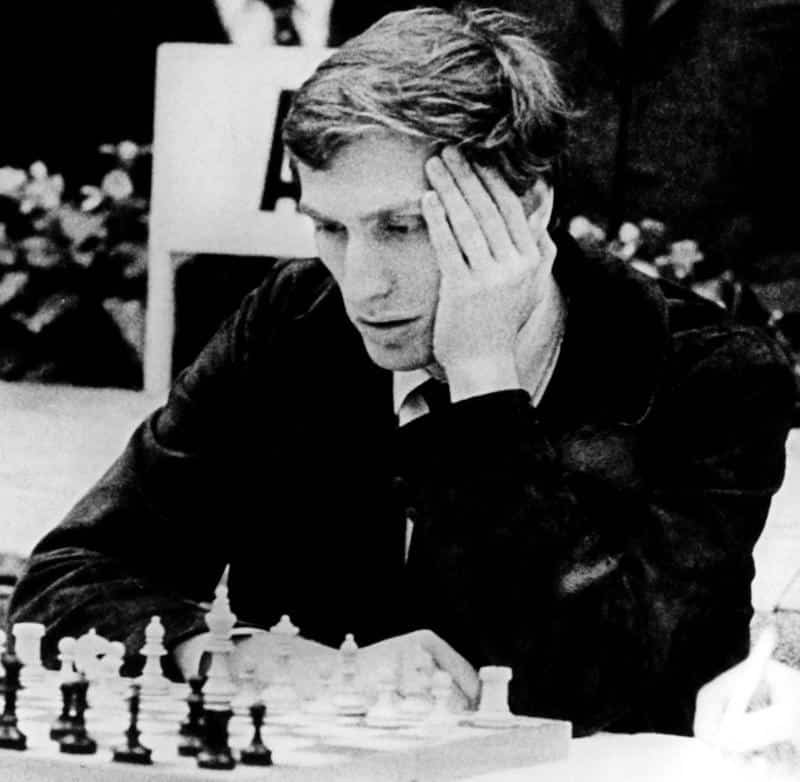

Shortly after, the world was to witness the Soviet domination of chess. Barring a few years, Soviet players ruled the roost from 1927 to 2006. After the Second World War, especially during the 1960s and 1970s, chess became a quasi-battleground for the Cold War. The Soviet administration actively promoted and poured resources into the development of chess and no one from any other country could rival the excellence of their players until Bobby Fischer came along.

Bobby Fischer and After

Bobby Fischer was, and still is, one of the chess world’s biggest legends. In 1956, at the age of thirteen, he beat one of America’s top players and never seemed to look back. In 1958, he became the youngest grandmaster at the time. His rise also brought more popularity to chess in the US. By 1972, when he played Boris Spassky for the World Championship title, he’d built up a large fan following for himself as well as the game. The match, held in Reykjavik, was tense (a tension many believe mirrored the tension of the Cold War) and high-profile and it even attracted significant international attention. In fact, the match was so popular in the US that a New York channel received a slew of complaints for airing the Democratic National Committee proceedings instead of the match.

Fischer‘s win was made even more historic by his refusal to defend his title the following year. He attributed his reluctance to FIDE‘s internal politics and conflicts. His refusal and subsequent withdrawal from public life added to his enigma. He emerged years later, in 1992, challenging Spassky to a private rematch in Montenegro, which he won again. Nonetheless, by visiting Montenegro, he ran afoul of the American state: he was charged with having violated economic sanctions imposed by the UN on Yugoslavia. Perceived as a controversial and alienating personality, he later accepted Icelandic citizenship and lived in Reykjavik until his death in 2008.

Rarely since the days of Fischer has chess been at the centre of American and international attention centred around politics. Even the introduction of chess computers could not captivate public attention in quite the same way Fischer had. FIDE itself has faced many challenges since, especially when Garry Kasparov, another world champion, split from it in 1993 to form his own association called the Professional Chess Association (PCA).

While the tournament circuit also seems to have fallen out of favour, chess still retains its aura. The game’s enduring attraction lies in the mental fortitude the game demands of its players. Additionally, many of the game’s biggest stars seem to have had fascinating and controversial personalities, which also plays a part in capturing public attention.

All this is not to deny that chess, when it is played competitively, is still a very intense sport. Competitive chess is also associated with a strong chess culture: cities like New York, St. Petersburg and Reykjavik are home to elite chess clubs and players. Chess is also popular and immensely competitive in Asia, especially India, China and Azerbaijan (though Azerbaijan, it must be noted, is a transcontinental country extending across Asia and Europe). The stakes game format is ideal even for street play. In fact, New York’s Central Park is a popular hub for exciting street matches.

Chess on the Screen

Chess provides great source material for fiction plots as well. A substantial number of films have been made about the game. The most notable recent release is Netflix‘s The Queen’s Gambit. Based on a bestselling novel, the series has triggered a wave of interest in chess. It has also helped push the issue of sexism in chess into the mainstream. In a sport dominated by men, the protagonist Beth Harmon makes an indelible mark with her strong style of play. The series also reflects the journeys of multiple female players and grandmasters, such as Judith Polgar and Maia Chiburdanidze. Beth‘s obsession with the game also brings to mind the dogged commitment of Lisa Lane, one of America’s top players during the 1960s.

Useful Links

- Science and Arts Education blog: https://stemeduconnect.

wordpress. com/ - Chaturanga: https://www.

chessvariants. com/ historic. dir/ chaturanga. html - World Chess Federation: https://www.

chesshistory. com/ winter/ extra/ fidehistory. html

Audio Version

Intro Music: Bomber (Sting) by Riot (https://www.

Relaxing Chill instrumental meditative | Arnor by Alex-Productions is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.