Board games are often seen as a way to bring people together. They’re a social activity, even for solo gamers. When we sit down to play, we fall into familiar rhythms of turns, actions and mechanisms. We don’t even need to share the same language. Playing board games is a time when gestures, shared goals, and the actions within the magic circle of the game itself act as a way for us to communicate. Board games themselves are like a shared language, where friendly rivalry, cooperative play and everything else sometimes conveys more than words ever can.

Listen to the Audio Version

Intro Music: Bomber (Sting) by Riot (https://www.

Over Oceans by Alex-Productions | https://onsound.

Music promoted by https://www.

Creative Commons / Attribution 3.0 Unported License (CC BY 3.0)

https://creativecommons.

Endless by Moavii | https://www.

Free To Use | https://freetouse.

Music promoted by https://www.

Survival Mode by Unheard | https://freetouse.

Free To Use | https://freetouse.

Music promoted by https://www.

Teapot by Lukrembo | https://soundcloud.

Free To Use | https://freetouse.

Music promoted by https://www.

Rules, Icons and Language-Independence

Modern board games are becoming increasingly language-independent, with only the rulebook requiring translation. The components themselves often use colours, symbols, and simple diagrams to guide players. Iconography and consistent visual cues mean that, once the rules are learned, the need for any language, spoken or signed, becomes almost irrelevant. Players from different countries may use a shared language, such as English, to introduce themselves, check if they’re all happy to play a particular game and maybe exchange a few pleasantries. However, once they sit down and the game begins, their superficial differences seem to just fade away. All they need now to communicate is the actions they take in the game.

Iconography can be particularly effective when it is intuitive and easily learned. The clear resource symbols in Catan, for example, help players negotiate trades with gestures alone. Even without a shared vocabulary, players can point to sheep and show two fingers, then point to wood and show four fingers, and the other player will understand what they’re trying to convey.

When publishers include rulebooks in multiple languages, the barrier to entry is also lowered. Everyone can learn the rules in their own language and refer back to them during the game without needing constant verbal explanation. Coupled with a clear, language-independent design, players’ confidence will increase, which is particularly important when someone worries that their understanding of language won’t be able to keep up with the rest of the group.

In fact, a clear rulebook and a clear language-independent design generally make any board game easier to learn and play. These games have a lower barrier to entry. Anyone who wants to play will find it easier, even if everyone speaks the same language. Yet, when people speak different languages, it’s vital that everything is clear.

The Shared Magic Circle

There is something else that turns board games into a sort of language of their own. Once a game begins, the day-to-day usually fades away, and the group enters the magic circle of play. Within that circle, the rules, mechanisms, and objectives act as a common reference point.

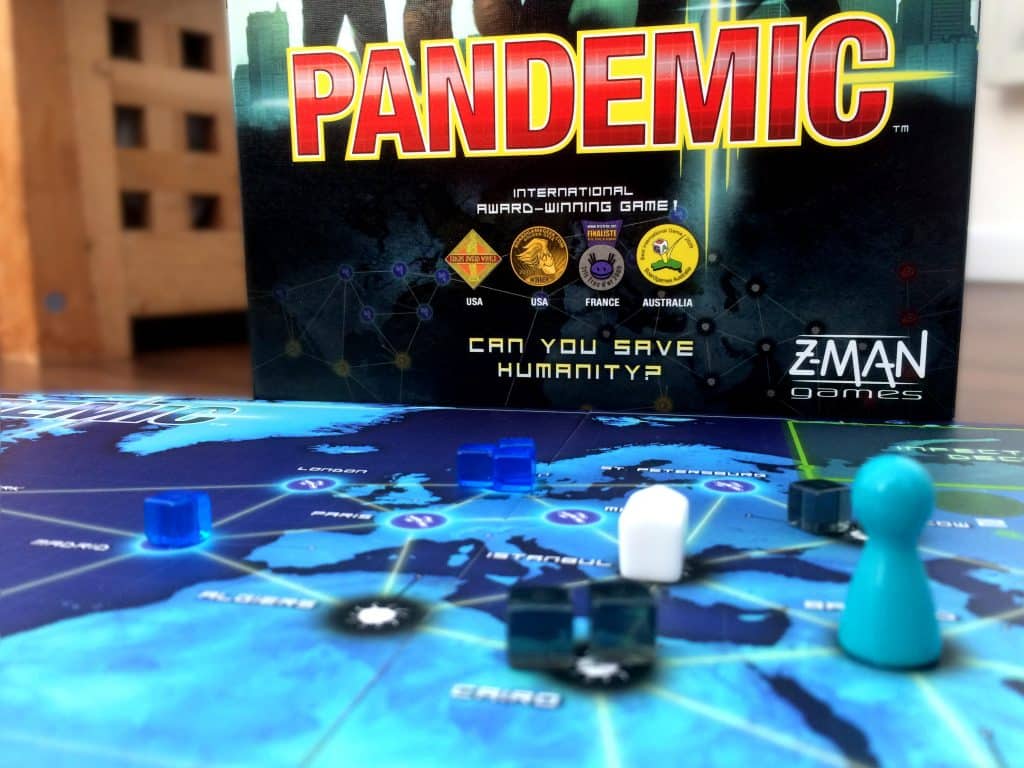

Cooperative games such as Pandemic demonstrate this beautifully. Players must work together to contain outbreaks, discover cures, and plan efficient responses to crises. Even when players do not share the same language, because all of the information is public, they can show each other cards and point at the board to indicate what they’re planning to do.

Cooperative games are possibly one of the best environments for those learning a second language. They are a safe space where mistakes might be frustrating, but in reality, they don’t carry any serious consequences. The shared objective makes even seemingly small interactions meaningful, because everyone wants the team to succeed. The game becomes the language, or at least the setting in which communication can take shape.

In my experience, the shared goal can also help reduce anxiety. When everyone is focused on a common goal, no one is judging anyone else, at least if the group doesn’t contain an alpha gamer who wants to boss everyone around, of course. The focus is on solving the puzzle of the game, not on grammar or pronunciation. That’s why I often recommend cooperative games for mixed language groups. They provide a unifying purpose that encourages contribution in whatever form each player is comfortable with. That feeling of a shared effort, grounded in the game’s structured world, makes communication feel natural and even enjoyable.

Non-Verbal Communication

Speaking of non-verbal communication. When people don’t speak the same language, gestures become a vital part of conveying meaning in any setting, as much as when playing board games. Gestures can narrow language gaps with surprising ease. Some games even encourage this in the way turns unfold that can be interpreted visually.

In Tapestry, for example, progress along tracks, placement of buildings, and playing of cards all communicate intentions before a single word is spoken. A player leaning forward and eyeing a particular track often reveals their next ambition long before they declare it verbally. The components provide a canvas for understanding that does not rely entirely on speech. Of course, Tapestry relies heavily on text, whether on cards or player boards. So maybe it’s not the best example, but I think you can see what I’m trying to say.

Visual communication allows players to express ideas even when a spoken language feels challenging. Something as simple as placing a building near a vital space, or pointing gently at a potential choice, can open dialogue that transcends vocabulary. Facial expressions and body language in response to someone else’s actions convey a lot of meaning, whether amazement at a clever move or sympathy for someone’s bad luck. These visual cues build rapport and create connections that words alone often struggle to properly frame, especially when someone isn’t familiar with a language.

Also, over time, players might pick up repeated phrases or begin to use small pieces of vocabulary that relate directly to the shared experience. I always love it when non-verbal cues and a board game’s structures create an environment where everyone feels included, because the game and the players’ in-game actions do so much of the talking.

Social Bridges Across Cultures

Board games can also create social bridges across different cultures. They form a safe space where people can come together and join in a shared experience. Board games provide structure and create a magic circle in which social situations can feel easier to manage. People unsure of their language skills can hide behind their in-game character or express themselves with the actions they take in the game.

Board games can also teach others about another person’s culture or background. Ofrenda, for example, can teach people about the altars so popular in Mexico. If someone brings a game from their home country, which is not well-known abroad, they can share a little bit of themselves and their culture. Even a traditional trick-taking game can allow players to learn about each other’s backgrounds.

Of course, cultural backgrounds often influence how people approach games. Usually, diversity enriches the board game experience. Players may interpret choices differently, value strategies based on personal preferences, or bring storytelling elements inspired by their own traditions. These can spark conversation, maybe with gestures, and contribute to a warm atmosphere of curiosity and discovery.

Lastly, when you play board games with the same group, you often develop your own shared language of table habits and in-jokes, which strengthen the bonds to the people around the table.

In the end, one of the things that makes board games so special to me is the way that they allow people to meet on equal ground. When language fades into the background and connection becomes the priority, the table becomes a place of genuine human interaction. Board games show us that communication is more than just words. It is a shared purpose and the willingness to meet others where they are.

Keeping the blog running takes time and resources. So if you can chip in, that would be amazing.

Useful Links

- Pandemic review: https://tabletopgamesblog.

com/ 2020/ 01/ 18/ pandemic-saturday-review/ - Tapestry review: https://tabletopgamesblog.

com/ 2019/ 11/ 09/ tapestry-saturday-review/ - Ofrenda review: https://tabletopgamesblog.

com/ 2025/ 05/ 10/ ofrenda-saturday-review/